This summer, I have been living at home in Boulder, Colorado, a true Mecca of environmental and social activism, hundreds of health food trends, outdoor adventures, and active lifestyles. Before I left for college, I lived in Boulder for six years, so it’s been amazing to be back for a solid chunk of time. Boulder is nestled right up against the Rocky Mountains, along Colorado’s Front Range. A defining mountain feature in Boulder is the Flatirons, which are essentially giant flat slabs of rock leaning against the foothills.

The Flatirons are part of a larger group of rocks called the Fountain Formation. This formation is made of sedimentary rock, which is basically sand and gravel that have accumulated over millions of years and eventually hardened into rock. The Fountain Formation was deposited around 280 million years ago as an ancient Rocky Mountain range eroded down to nothing. The world was almost unrecognizable 280 million years ago:

The continents were not in the same configuration as they are today due to something called plate tectonics. To learn more about plate tectonics and how it works, check out a previous post I wrote about the Geology of Big Sur here.

So if the Flatirons were deposited horizontally, as flat layers of sedimentary rock, how did they get tilted up almost 60 degrees? They did lie flat for a very long time, and then were uplifted when the Rocky Mountains formed, kind of like someone pushing a trapdoor open from beneath.

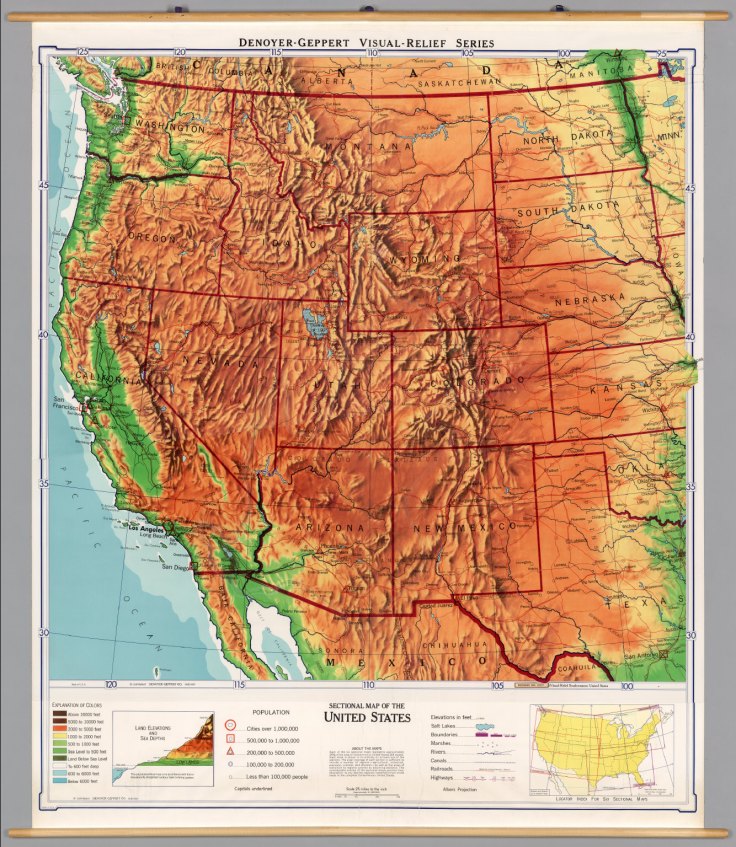

The Rocky Mountains that we know today were formed 65 million years ago. But how? Most mountain ranges on our planet are located within 200-400 miles of a plate boundary. But in the case of the Rocky Mountains, the nearest plate boundary is along the West Coast of the United States, 1000 miles away:

The Pacific Plate boundary (the one that runs through California) is a subduction zone, which means that one plate slides under the other. Most subduction zones look like this, where the subducting plate goes beneath the other at a very steep angle:

This is what causes most mountains to be located near a plate boundary – the subducting plate doesn’t influence the surface layer of crust for that long before disappearing into the mantle. The Pacific plate boundary looks a bit different:

As you can see, this subduction occurs at a much shallower – in fact, a nearly horizontal – angle. Because the bottom plate is located much closer to the surface layer of crust than in the steep-angled subduction zones, it affects what the surface looks like for longer. As the plate keeps moving, and keeps sliding underneath, it creates mountains much farther away from the plate boundary than is normal. There is more friction between the two plates in this case, since they are close together, so there is the potential to make very tall and large mountain ranges. This is exactly what happened in the formation of the Rocky Mountains.

Colorado is one of the best states, in my opinion, for experiencing all that the Rockies have to offer. It is home to the highest number of “14-ers” (mountain peaks that are at least 14,000 feet above sea level) in the mainland U.S. If all goes well, I will climb my first 14-er in a couple weeks! Also, Boulder is just an hour’s drive away from the famous Rocky Mountain National Park. I went backpacking there twice this summer, and here is a collection of some of my favorite scenes from the Park:

This summer, I also got the chance to visit one of Colorado’s lesser known National Parks: Great Sand Dunes. This park is essentially an enormous pile of sand nestled between the San Juan Mountains and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Sediment eroded into the valley, and after lakes formed and dried up again, all the loose sediment was picked up by southwesterly winds and pushed up against the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, where it still sits today. You can watch a short animation about the process here.

Great Sand Dunes National Park is one of the most magical and unique places I’ve ever been in my life. There are very few places where you can see such huge, magnificent dunes against a beautiful mountain backdrop.You can hike up to the top of the dunes, where you can see them stretching onwards for miles, and many people camp at the park overnight and sled and snowboard down the dunes. Here are some photos from my time there this summer:

It’s been such a treat to go on so many adventures in my beautiful home state of Colorado, and appreciate the unique geology and incredible natural spaces that have arisen because of it!

September 6, 2015 at 1:05 pm

The Andes Mountains in South America were also formed the same way as the Rockies. You can learn more about it by reading this paper: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0012821X10005856

LikeLiked by 1 person